How different types of exercise affect our brains

How different types of exercise affect our brains

Exercise helps us maintain not only our physical health, but also our mental health. We tell you what types of activity improve memory and concentration and why your brain will thank you for a combination of different types of exercise.

Brain and exercise: a direct correlation

To build muscle, you have to pull iron. Yoga develops flexibility and helps you relax. Running gets rid of extra centimeters on the waist and is one of the fastest ways to tighten the body and lose weight. Various fitness routines help us get healthy and focused and create the perfect body. They are something of an energy bomb and uplifting.

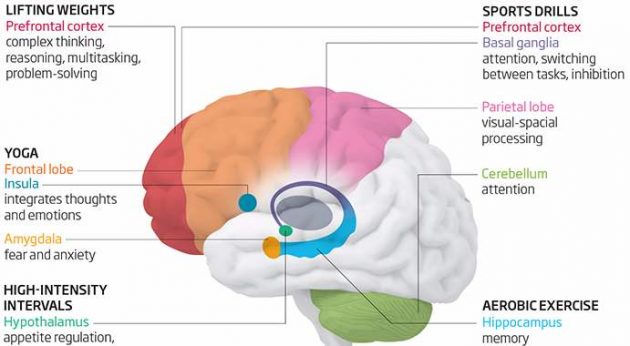

Thanks to recent research, we can develop the brain in the same way that we develop the body. Different physical exercises affect not only the body, but also the brain in different ways: each one activates a specific area.

Physical activity makes us more intelligent, delays the onset of senile dementia, and helps fight depression and Parkinson’s disease. This is because blood saturated with oxygen, hormones and nutrients gets to the brain faster. All this makes it as healthy, efficient and strong as the heart and lungs.

Researchers decided to find out exactly which areas of the brain are affected by high-intensity interval, aerobic and strength training, yoga, and other sets of exercises.

Does it make sense to speed up or, on the contrary, is it better to slow down? Going to the gym for strength training or doing yoga? It all depends on the goal you are pursuing: to become more focused before an exam or difficult work, to relax or to quit smoking.

Effects of exercise on memory and executive functions

Aerobic exercise

Speculation about the effects of specific types of exercise on the brain emerged 15 years ago through experiments on rodents. Scientists found that mice that actively spun a wheel formed new neurons in the hippocampus, the area of the brain responsible for memory. Exercise made hippocampal neurons pump out a special protein – brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which promotes the formation of new neurons. The experimental mice improved their memory, allowing them to navigate the maze more easily.

The study was soon transferred to humans.

Older adults who did aerobic exercise three times a week for a year had better memory. Their blood levels of BDNF protein were higher, and more active formation of new neurons was observed in the hippocampal region.

The finding that running and aerobic activity help fight senile dementia and prevent Alzheimer’s disease was welcome news. The search for other treatments and prevention of many cognitive impairments has been rather slow, and existing medications have had unpleasant side effects.

Power Exercise

Teresa Liu-Ambrose of the University of British Columbia (Canada) decided to go further and explore this topic in more detail. She wanted to find out exactly what parts of the brain are affected by certain exercises, and was looking for ways to slow the development of dementia in people with cognitive impairments. In the process, Teresa Liu-Ambrose became particularly interested in the effects of strength training.

To test her idea, Teresa Liu-Ambroz conducted a study involving 86 women with moderate cognitive impairment and compared the effects of aerobic exercise with strength training. Teresa evaluated their effects on memory and executive functions, which include complex thought processes (reasoning, planning, problem solving and multitasking).

One group of subjects exercised twice a week for one hour of strength training, while a second group walked briskly, which provided sufficient exercise. The control group did only stretching.

After six months of training, members of the strength-training and brisk-walking groups showed improvement in spatial memory – the ability to remember one’s surroundings and one’s place in them.

Each exercise had its own positive effects.

Members of the strength-training group showed significant improvements in executive function. They also performed better in tests of associative memory, which is typically used to link representations and circumstances to one another.

People who did aerobic exercise significantly improved their verbal memory and their ability to remember and find the right words.

Subjects who did only stretching showed no improvement in memory or executive functions.

Combining different types of activities

If the benefits of strength training and aerobic exercise are different, what happens if they are combined?

To solve this problem, Willem Bossers of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands divided 109 people with dementia into three groups. One group went out for 30-minute brisk walks four times a week. The combination group took half-hour walks twice a week. In addition, people in this group came for strength training twice a week. The control group had no exercise.

After nine weeks, Bozers administered a comprehensive test that measured the experiment participants’ problem-solving ability, inhibition (inhibition), and processing speed. After processing the results, he found that the combination group performed better than the aerobic and control groups.

From the results of the study, we can conclude that just going out for a walk is not enough to improve cognitive health for the elderly. They need to add a couple of strength training exercises to their schedule.

Improved focus

The positive effects of exercise extend not only to those with problems, but also to healthy adults. After a year-long experiment with healthy older women, Teresa Liu-Ambroz found that strength training at least once a week resulted in significant improvements in executive function. Balance exercises and simply toning exercises had no such effect.

Combining strength training with aerobic exercise is ideal because weight work releases insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a growth hormone that is produced in the liver. It is known for its effect on communication between brain cells and promotes the formation of new neurons.

In addition, aerobic exercise increases BDNF protein production, while strength training lowers levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that increases in the brains of older people with dementia.

By combining strength and aerobic exercise, you get a powerful neurobiological cocktail. Unfortunately, studies have not yet determined the duration of the healing effects of exercise, but they indicate clearly enough that older adults must exercise to maintain mental health.

Other studies show how different exercises affect a child’s development and abilities. For example, if you want your child to concentrate for at least an hour, it’s best to let him or her run a couple of laps. Twenty minutes of walking has an immediate positive effect on children’s attention and executive functions. Running and dancing have about the same effect. Also, walking at a brisk pace helps hyperactive children with attention deficits focus on the task at hand.

Exercises that aim to develop certain skills (for example, coordination of movements) worsen attention. A large number of rules and special exercises can be too difficult for children, especially before tests or in situations that require concentration. However, these exercises have a positive effect on the development of concentration in perspective.

Maria Chiara Gallotta from the University of Rome (Italy) found that games with complex coordination of movements, such as basketball or volleyball, help children do better on tests that require concentration.

The cerebellum is the part of the brain that is not only responsible for coordinating movements, regulating balance and muscle tone. It is also involved in concentration. Working on complex movements activates the cerebellum, which, in interaction with the frontal lobe, increases attention.

Moreover, children who participate in sports have larger hippocampus and basal ganglia than in inactive children. These children are more attentive. The basal ganglia are a group of structures that play an important role in movement and goal-directed behavior (turning thoughts into actions). They interact with the prefrontal cortex and influence attention, inhibition and executive control, helping people to switch between two tasks.

Adults can also benefit from performing challenging sports tasks. Studies in Germany have shown an increase in basal ganglion volume after coordination exercises such as keeping balance and synchronizing arm and leg movements. The same effect was observed with ropes and balls.

Synchronization exercises improve visual-spatial information processing, which is necessary for determining distance in the mind. For example, this might be estimating the time to cross the road before the red light comes on.

Another explanation is articulated in research conducted by Tracy Alloway and Ross Alloway at the University of North Florida (USA).

Scientists have found that a couple of hours of activity, such as climbing trees, balancing on a crossbar or running barefoot, has a significant effect on working memory.

Operative memory is responsible for the ability to hold information in your head and manipulate it at the same time. It processes information and decides what is important, ignoring what is irrelevant to the work you are doing at the moment. Your working memory affects almost everything you do.

So what’s so special about climbing trees or balancing on a crossbar? Researchers have found that only a combination of the two different activities yields positive results. Both involve a sense of proprioception (feeling the position of one’s own body parts relative to each other and in space).

There should also be another element – calculation of the distance to the next point, navigation or movement in space. A positive effect will be produced by an exercise in which one must simultaneously move and think about where and how to do it.

Appetite Control

One of the latest sports trend is high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which involves alternating high-intensity and low-intensity exercises. These short workouts offer the same benefits as the more usual longer sessions.

Interval training has its own advantage: short bursts of activity reduce hunger.

To test the effects of interval training on appetite, scientists from the University of Western Australia invited overweight men to participate in an experiment. Scientists asked the subjects to ride a bicycle for 30 minutes each for three days. The intensity of the exercise had to be different each time. On the fourth day, the subjects rested.

It turned out that after the most intense workout and during the time remaining until bedtime, the men ate less than usual. Moreover, their appetite on the next few days was half as much as on the days after the moderate-intensity exercise and after the rest day.

One explanation for this phenomenon could be that exercise lowers levels of ghrelin, the hunger hormone. It is responsible for communicating with the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that regulates the feeling of fullness and tells you when your stomach is empty. Once the stomach is full, ghrelin production stops and the feeling of hunger disappears. After high-intensity exercise, ghrelin levels were lowest in the body.

The bottom line

So, what is worth remembering from this body of research for those who want to pump their brains with exercise?

Running and aerobic activity help fight senile dementia and prevent Alzheimer’s disease, improve verbal memory, the ability to remember and find the right words.

Strength training has a positive effect on the executive functions of the brain, that is, the planning and regulation of conscious actions.

Games with complex coordination of movements help children concentrate better.

Interval training helps control appetite.

The most positive effects for the brain can be achieved by combining different types of activity, such as aerobic and strength training.